Introduction

Jupyter notebooks are really useful interactive coding environments that bring along documentation capacity in readable, non-code format. This means we can use Jupyter notebooks to develop and test code and legibly explain what’s happening all in the same place. So far so good; and there are lots of great videos online showing this environment in action.

If you would like to build a Jupyter notebook environment (a notebook server) on a cloud machine: You’re in the right place. The directions here are “from the ground up” and serve a second purpose as well, which is (we at CloudBank hope) to de-mystify building on and using the cloud.

Before we begin, however: Remember that cloud providers like to do things for us “as a service”. You can get into Jupyter notebooks in this manner in Azure or on the Google Cloud Platform or on Amazon Web Services or on the IBM Cloud etcetera. If you choose to go this way there are two things to check on: The cost for the value-added service and whether the results of your work will be transferrable to other environments / platforms.

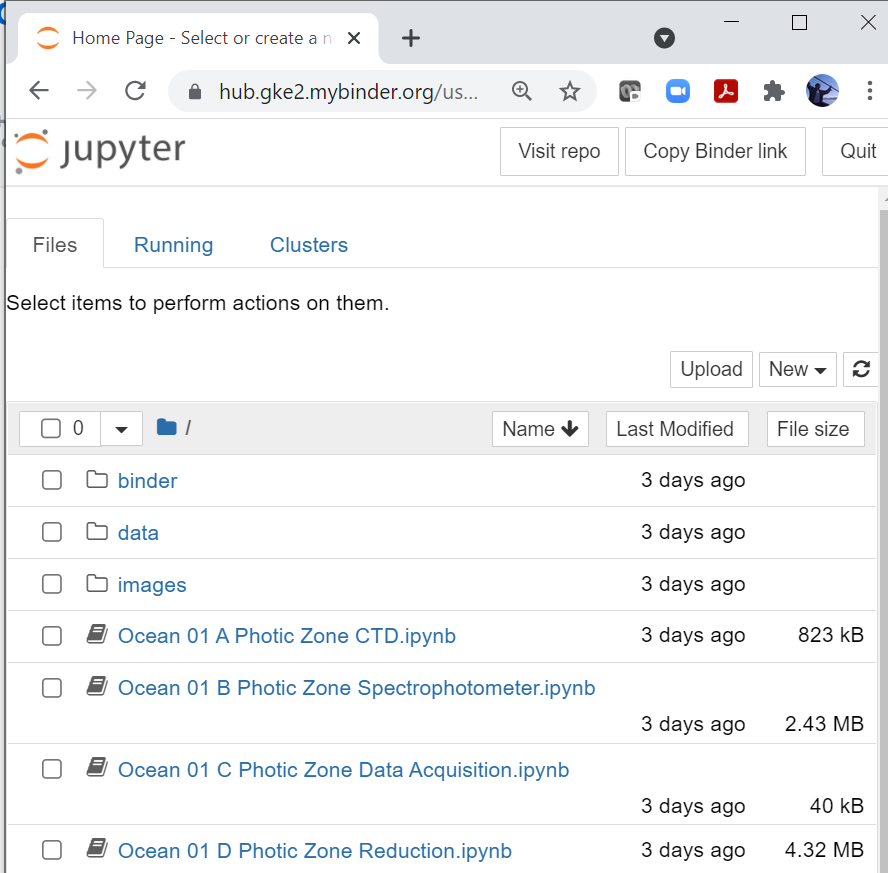

That said, we’ll proceed with the Do It Yourself On The Cloud approach. Here is an example of a notebook server browser interface.

- Ok now what is the plan?

- (and while we are it it: How does one simplify the bash terminal display?)

- Why does this require instructions?

- Let’s do it!

What is the plan?

Learning to compute on the cloud includes understanding machine images: Snapshots of an entire operating system including installed software, customization, code and data. This CloudBank solution serves two purposes: It introduce machine images and it demonstrates using a cloud virtual machine (herein VM) as a traditional desktop–possibly quite a powerful one–for running a Jupyter notebook server. The interface to this working environment will be via a web browser on our Local machine. We move information back and forth securely from Local to Cloud using an ssh tunnel.

Why instructions are necessary

At a high level we are configuring a research computer. Because it is on the cloud there is some extra vocabulary involved and some extra steps, starting with securing a cloud account. There is enough complexity to merit a walk-through. Here’s the narrative:

- A researcher decides to work on the public cloud; and gains access…

- Cloud access agreements commonly are called ‘accounts’ or ‘subscriptions’

- CloudBank uses the term billing account

- Using a browser interface the researcher starts a dedicated cloud VM and logs in

- The researcher configures the VM as a Jupyter Lab notebook server supporting a Python kernel

- Other useful tools / libraries / packages / datasets are installed

- The researcher tests the Jupyter Lab server by connecting via browser

- This makes use of a secure connection called an ssh tunnel

- The researcher uses cloud management tools to create an image of the VM on the cloud

- Unlike a container, this image is cloud-specific (not transferrable to other clouds)

- The researcher Terminates (deletes) the VM: It is no longer available

- The stored image persists and can be used to start up a new VM

A VM may be in one of two states: Started or Stopped. We pay for a VM by the hour: Only when it is Started. Stopped is like having the power turned off: You can resume using it later without loss of data. Terminating a VM means the VM no longer exists: Everything is gone.

Starting a VM from an image recreates the machine in its state when the image was created. When you do this you have a choice of which type of VM to use for the image. You can use a cheap low-power VM if you do not need a lot of computing power; say you just want to write and test some code. Or you can choose a powerful (more expensive) VM if you have some heavy computation to do.

Notice that you may start many VMs from a single image. Your collaborators may use an image to start their own VMs as well. This means that customized work environments are easy to replicate and share.

Key concepts

- Authentication

- Authentication is “logging in”, i.e. you are authenticated to use a resource on the cloud

- On the cloud there are (at least) three authentication paths: Username/passord, login keypairs and IAM Access Keys

- Authentication is generally credential use over a secure connection

- The secure connection is built into applications like ssh as a protocol: It just works.

- The credential may be a file containing long text strings: Guard as if they are passwords to your bank account

- Cautionary tale: An Access Key file for your cloud account can be used to automatically run tasks

- This means that someone with your access key can easily spend $15,000 in one hour mining bitcoin

- Do not place credentials on Virtual Machines that will be used to create images per this walk-through

- Cautionary tale: An Access Key file for your cloud account can be used to automatically run tasks

- Virtual Machines (VM / VM instance / “EC2” on AWS, “Google Compute Engine” on GCP, “Azure VM” on Azure)

- Wide variety of instance types to choose from.

- Any given instance type will have associated memory, processing power and storage (see below).

- The cost of the instance – per hour – varies with these characteristics.

- On the AWS console you select the EC2 service and then Launch Instance

- This runs a launch wizard: First step is to choose an operating system image

- Second step is choose instance type

- Search on

cost <instance-type> <cloud provider>to check rate per hour

- Search on

- Wide variety of instance types to choose from.

- Block storage is the term used for a disk volume: Root operating system, data drives etc

- On AWS this is called Elastic Block Storage (EBS)

- AWS also supports temporary disk storage through the instance store

- Distinguish between Elastic Block Strage (EBS) and (ephemeral) instance store volumes

- Instance store volumes evaporate on Stop/Start. EBS volumes persist through Stop/Start.

- Additional storage modes:

- AWS EFS (Elastic File System) shared by multiple instances; ~ UNIX NFS

- AWS S3 Object Storage

Walk-through

Again these use AWS as the “example cloud” but these notes will apply broadly to any cloud. The short version describes what to do with scant attention to specifics. The extended version is more comprehensive.

Short version

- Install a bash shell on your Local computer (laptop, dekstop etc)

- Start a cloud VM, note three things:

- the generic VM username (here we use

ubuntu) - the ip address of the VM (here we use

12.23.34.45) - download the key pair file to Local (here we use

keypair.pem)

- the generic VM username (here we use

- Assign the VM a stable (static) ip address

- This ip address does not change even when you stop and re-start the VM

- AWS: Use the Elastic IP service. GCP and Azure: The term is static external IP.

chmod 400 keypair.pemandssh -i keypair.pem ubuntu@12.23.34to log in to the cloud VM from Local- From the command line on the cloud VM install

miniconda,jupyterand other Python libraries - Use

git clone https://github.com/organization/repositoryon the cloud- Need a working example? Use organization =

cloudbank-project, repository =ocean

- Need a working example? Use organization =

- On the VM: Start a Jupyter Lab notebook server as a background process with browser display disabled

- Example command to listen on port 8887:

(jupyter lab --no-browser --port=8887) & - Note the token string printed by the Jupyterlab start-up process

- Example command to listen on port 8887:

- On Local: Create an

sshtunnel associating Local port 7005 with VM port 8887- Example ‘ssh -N -f -i keypair.pem -L localhost:7005:localhost:8887 ubuntu@12.23.34.45’

- On Local, in a browser address bar: Enter

localhost:7005and at the prompt enter the token string- This connects to the Notebook server on the cloud VM via the ssh tunnel

- Test out some notebook functionality; verify that the Python kernel runs etcetera

- Stop and re-start the VM and again test functionality

- Stop the VM and create an Amazon Machine Image (AMI)

- Terminate (delete) the VM

- Re-start the VM from the saved image and again test functionality

- Note that the development of code within a

gitrepository supports back-ups and collaboration - A VM to be used for extended time (days or longer) is a candidate for a daily auto-Stop

- On AWS: CloudWatch and Lambda functions are commonly used for this purpose

- This action prevents charges from accruing overnight when the VM is not in actual use

- Use the AWS console to make the VM machine image (AMI) available to other people

Extended version

- Log on to the AWS console and select Services > Compute > EC2 > Launch Instance

- This may also be done with the Command Line Interface (CLI) for AWS or using an API such as

boto3

- This may also be done with the Command Line Interface (CLI) for AWS or using an API such as

- Run through the launch Wizard; here are some details by example:

- Image: 64 bit x86 Ubuntu Server (username =

ubuntu): Bare machine image, just the OS - VM:

m5ad.4xlarge, cost $1.00 / hour in Oregon at time of writing- This instance type includes two 300 GB instance store volumes (temporary storage)

- Data on these volumes is temporary, will evaporate: Don’t put anything important here

- Remember to Stop or Terminate this instance once you start it (and know the distinction)

- Zombie resource charges happen when we forget about a VM that keeps running

- This instance type includes two 300 GB instance store volumes (temporary storage)

- Configure instance: Default values

- Make the root volume larger (say 100GB) to create some working space

- Add Tags: Added key values

Name,Project,Date,Owner, etcetera as appropriate - Configure Security Group: Default values

- Review and Launch: Create a keypair file

keypair.pemand download it to Local - Launch: Note resulting ip address of the VM; let’s say it is

12.23.34.45

- Image: 64 bit x86 Ubuntu Server (username =

From my own computer log on to the AWS EC2 instance

- Relocate the downloaded keypair file to my

bashhome directory chmod 400 keypair.pemis a permissions change applied to the keypair file- Connect with the vm:

ssh -i keypair.pem ubuntu@12.23.34.45

On the EC2 instance (VM) mount any added storage drives

- Search engine: ‘AWS EC2 EBS mount` gives this instructive link

Install the Jupyter Lab notebook serve

- Install Anaconda or Miniconda

- search

install Anaconda Linuxand follow the instructions - Once the download path is determined I used

wgetto download the installer on the VMwget https://repo.anaconda.com/archive/Anaconda3-2020.07-Linux-x86_64.sh

- On Ubuntu I installed in the

/home/ubuntudirectory and needed to add the path forcondaexport PATH=~/anaconda3/bin:$PATH

- Once Anaconda is installed: use the

condapackage manager to install Jupyterlab conda install -c conda-forge jupyterlab

- search

Configure the machine for research

- Install software packages

- The following are example installation commands (geoscience-oriented)

conda install xarrayconda install -c conda-forge cmoceanconda install botoconda install netcdf4conda install -c conda-forge ffmpegconda install networkxpip install utmsudo apt install nodejsworking towards widgets…

- Import datasets:

sftp -rfrom the data directory of a data source computer requirements.txtorenvironment.yml:pip freezeand related links needed

- The following are example installation commands (geoscience-oriented)

Create an image (AMI) of this Virtual Machine

- On the AWS console: EC2 ‘running instances table: Locate and select this instance

- When you run the Create Image process the VM will be Stopped

- Actions menu > Image > Create Image

- Be sure to attach extensive metadata (typically add Tags) to the AMI to make it recognizable

Share the AMI with other AWS accounts

- On the AWS console > AMI listing (see left sidebar) > Permissions editor

- Add the AWS 12-digit account of a destination account where you wish this AMI to be available

Terminate the VM

- This step established that it is safe to Terminate a VM backed up by a machine image

- Do this as a proof of concept operation

- WARNING: This will completely delete this EC2 instance

- You could Start a new EC2 instance from the AMI prior to the Terminate just to be careful

- You can verify everything is preserved as you expect in this new instance

- At this point the AMI has been demonstrated as correct and you can Terminate both EC2 instances

- On the AWS console > EC2 ‘Running Instances’ table: Locate and select an instance to Terminate

- Actions menu > Instance State > Terminate and confirm

Notes

- Once per month updates is a typical pace

- Update the operating system:

sudo yum update - Create a new AMI and manage your AMI catalog to avoid zombie AMIs

- On the VM:

ps -ef | grep jupyterto see if the server is running jupyter nbextension enable --py widgetsnbextension

left off here

what follows is a copy paste of the original student hands-on for restoring and using a VM. As such it can be reduced down to a much smaller section here.

CloudBank Solution Repo: Research Computing and Cloud Images

This tutorial introduces you, the researcher or student, to using a virtual machine image on the cloud as a basis for research computing. This page describes using an image that has already been built for you. If you want to see how to do the preparatory build: Look into the creating_an_image sub-folder.

You may be familiar with a zip or tar file containing an entire directory. A machine image is analogous; think of it as a zip file of the entire computer’s contents from operating system to home directory to code to data files. The idea is that once a cloud Virtual Machine (VM) is configured for use: It can be stored as a machine image. This image is then un-packed back onto a Virtual Machine. The image is used to creating a working research computing environment for a scientist to use.

Our specific example here takes advantage of the Jupyterlab notebook server. This page is a tutorial for going from a pre-built Linux environment with Jupyterlab installed as an image and reconstituting it on the AWS cloud as a Virtual Machine. We will use a secure tunnel called an ssh tunnel to enable you the researcher to connect to the Jupyterlab server through your web browser.

In the sub-folder called bootstrap we go through the process of building this machine image.

In the sub-folder called waterhackweek we go from the rebuilt Jupyterlab VM to cloning a repository of notebooks on the VM for a particular research topic.

Important remark on cost management

In what follows on this page: The VM has a single disk drive (filesystem) with a fairly small capacity of 32 Gigabytes. However it is common practice to create images that bundle large datasets. The sub-folder bootstrap tutorial spins up a Virtual Machine, for example, that has 200 GB of block storage (disk drive) volume mounted as two data filesystems. This allows the image builder to include a moderately large dataset with the image and provide some working space as well.

Our point of emphasis here – as with all cloud resource allocation actions – is that one should understand and track the costs associated with cloud resources. ‘Block’ or ‘disk’ storage – for example – runs about $20 per month for 200 GB.

Again our main admonition: The cloud is very powerful but it is important to understand and manage the cost of using it.

Outline

- In what follows please customize your resources by substituting your own name for

hedylamarr. - Obtain credentials to log in to the cloud console: Contact cloudbank for details

- Identify the proper image and use it to jumpstart a Virtual Machine instance

- Log on to this instance and start up a Jupyter Lab server

- Create an ssh tunnel from your computer to this server

- Use your browser to connect to the Jupyter Lab and use this to explore some data

For Windows Users

A brief interruption anticipating a possible issue: Further down we are going to build something called an “ssh tunnel” to use our Virtual Machine as a Jupyter notebook server. If you are doing this on a PC running Windows: No problem, that’s perfectly feasible but Windows does not natively make this Linux-y step trivial. So be ready: We will introduce the idea of installing a small Linux bash shell on the Windows PC. It is a bit of a “yet another step, really??” situation but on balance it can help save time and avoid frustration. Instructions are here.

Connecting to a Jupyterlab server built on a cloud Virtual Machine

Suppose we would like to visually explore some (ocean) data. This data took years to collect and months to bring together in one location. Hopefully it takes less than an hour to deploy and connect to a Jupyterlab notebook server on the cloud.

Prerequisites: Cloudbank credentials to connect to the cloud and an available

bashshell.

We are using in this case the AWS (Amazon Web Services) cloud. You will log on to the AWS console, start a Virtual Machine (called an EC2 instance) and on that machine start a Jupyterlab server. If you were starting from nothing you would be installing Python packages and importing datasets. Our objective here is to avoid all of that by using a pre-built environment stored on the cloud as an image. Once you have identified this image you can start it on virtually any size machine; from a small cheap one say costing $0.04 per hour to a very powerful computer that might cost $2.40 / hour or more. Cloud users choose a computer based on computational needs.

Once the computer is running (with everything pre-installed) you will create an ssh tunnel. This is a secure connection that associates a local address on your local comoputer with the Jupyterlab server running on the cloud VM. By connecting through this tunnel the cloud VM becomes the backing engine for exploring the data.

The procedure is presented in 13-or-so steps with interspersed comments. Upon completion you will have your own data science research environment.

Procedure

-

Log on to the AWS console using your credentials; and be sure to set your Region (upper right drop-down) to Oregon o Sidebar: You can choose Services (upper left) to see a listing of services, i.e. what you can do on the AWS cloud

-

Navigate to Amazon Machine Image choices (AMIs): Services > Compute > EC2. Then choose AMIs from the left sidebar.

-

In the upper left drop down menu of the AMI pane select ‘Private Images’ (it may say ‘Owned by Me’ or ‘Public Images’ by default). When ‘Private Images’ is selected, you should see an AMI listed called

jupyter1-cb. Select this AMI by clicking on it so a blue dot appears at the left edge of the table. -

Choose Actions > Launch. Choose a VM type

c5.large(you may have to scroll down a bit to find this). Choose Review and Launch at the bottom right.

WARNING: If this tutorial is a class-sized activity there is a potential collision scenario. Let’s take a moment to outline this and how to resolve it.

The AWS EC2 Launch Wizard goes through seven steps. Step 6 involves choosing a Security Group. This SG is given a name by default; and a classroom full of people will get the same default as they proceed. So the way to avoid this (which will obstruct the next couple of steps) is to click on the Security Group step (step 6) and give a name for the Security Group that is unique. As below with keypair and instance names the best choice for a Security Group name is simply

yourname. In our instructions we use the namehedylamarras an example of your name. Now you can proceed to step 7 of the wizard; which is step 10 in this procedural.

-

Choose Launch at the bottom right. In the ensuing keypair dialog choose Create new keypair and name it

hedylamarr. This will be the key to identifying your instance and logging in to it in what follows. Download the keypair file you generated; then click Launch Instance in the dialog box. -

Continue in the AWS console: Click View Instances at the lower right. This takes you to a table of EC2 instances (Virtual Machines), where one instance is listed per row. Therefore one of the rows in this table should be your instance.

Class strategy remark: You now have a Virtual Machine (“EC2 instance”) on the public cloud. If you are in a class with many people doing the same thing at the same time it can be difficult to identify which instance is your VM. Once you identify your instance: Name it using

yourname.

-

Locate your instance by the key name: In the table of instances scroll right to find the

Key namecolumn. Scan down this column for the keypair you used to identify the row for your EC2 instance. Return to the left-most Name column of this row – the row for your instance – and hover your cursor to bring up a pencil icon in the “Name” column. Click on that and name your instance appropriately. -

One the instance status dot changes to green (running): Note its

ip addressin the instance table. Here we take this to be12.23.34.45as an example.

Now we are ready to log in to this VM or EC2 instance from a bash shell. Our main goal on the instance is to start a ‘quiet’ Jupyterlab session. There will not initially be a browser interface; that comes a little further down. Once the Jupyterlab server starts it will print a token, a long string of letters and numbers used to authenticate; so be prepared to copy that to a text editor for a few minutes.

- On your computer: Open a

bashshell and ensure the keypair filehedylamarr.pemis present in your working directory. Issue achmodcommand to give the keypair file limitedrwxpermissions:chmod 400 hedylamarr.pem.

If running Windows on your local computer: You may need to install or enable the native

bashshell. As an alternative you can install an Ubuntubashshell. In either case it is useful to realize that the home directoy of this shell is not the same location as the Windows User home directory. Ifhedylamarr.pemwas downloaded toC:\\Users\hedylamarr\Downloads: Move it to yourbashhome directory, for example using this sequence of commands:

bash> mv /mnt/c/Users/hedylamarr/Downloads/hedylamarr.pem ~

bash> cd ~

bash> chmod 400 hedylamarr.pem

The

sshcommand insists the authentication keypair filehedylamarr.pemhave User read-only permission, Files in the Windows User area are not amenable tochmod; so we relocate this file and proceed inbashfrom~. These details can very frustrating so we go to the trouble to elaborate this here.

- In bash run

ssh -i hedylamarr.pem ubuntu@12.23.34.45to connect to your EC2 instance. (Use the correct ip address.) Respondyesat the prompt to complete the login. Note that your username isubuntuand you have the ability to run root commands usingsudo.

If you have configured the image using (for example) the tutorial in the

bootstrapsub-folder: You may wish to spend some time looking around to ensure the instance is configured as expected. For example if there are additional data disks you can check to see these have been mounted properly.

- On the command line of your EC2 instance issue

(jupyter lab --no-browser --port=8889) &After about one minute this command should produce multiple lines of output including atoken string.

...token=ae948dc6923848982349fbc48a2938d4958f23409eea427

...token=ae948dc6923848982349fbc48a2938d4958f23409eea427

Copy this string to a text editor for later use. If you lose this token just log on to the instance where it is running and issue jupyter notebook list to see it. Issue exit to log out of your cloud instance.

Note: The Linux structure

(command) &causescommandto run as a background job. This allows you to log out of your instance, leaving it to function as a Jupyterlab server.

Note: The above token is used the first time connecting to the Jupyterlab server. It may not be used in subsequent sessions but it is worth keeping it around. If it is lost for some reason: Re-start the Jupyterlab server on the VM and re-copy the token.

- In the

bashshell issuessh -N -f -i hedylamarr.pem -L localhost:7005:localhost:8889 ubuntu@12.23.34.45. (Make appropriate substitutions.)

This

sshcommand creates an ssh tunnel to the EC2 instance running the Jupyterlab server. You associate a location on your own computer (localhost:7005) with the connection point on the EC2 instance (12.23.34.45:8889). The number trailing the colon, called a port, acts as a qualifier for the connection.

- In your browser address bar type

localhost:7005. This should change tolocalhost:7005/lab?. When prompted for the token paste in the token string you copied earlier. You should now see a Jupyterlab environment. When using the instructional image for this tutorial there should be a notebook listed on the left calledchlorophyll.ipynb. You may click on this notebook to open it and explore the contents.

Idiosyncratic Cloud Notes

- To add a “data disk” to the VM allows us to create and manage additional storage capacity on a VM

- Link: Mounting storage volumes on AWS

- These persistent drives are called Elastic Block Storage (EBS) volumes on AWS

- AWS EC2 VMs may also feature instance store volumes equivalent to

/tmpstorage: Nothing persists here.

- Updating Anaconda and the machine image operating system

- Once per month is a common Anaconda update tempo…